The Greatest Race in the World

14 min readJust after the crest of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, the longest and highest climb of the New York City Marathon, around mile one, an MTA Bridges and Tunnels employee yelled some encouragement to those of us in the final starting wave of the race as we jogged across the span, almost 700 feet in the air, Manhattan taking up the horizon to the left, Brooklyn and open ocean to the right.

“Come on,” a voice barked from a group of guys in safety yellow sitting on the back of a truck as I passed.

“We’ve been out here all morning,” he continued. “It’s freezing.” He was right—it was a chilly morning, and there aren’t many places on the bridge to get out of the cold breeze. The encouragement was starting to turn into half-support, half-joke. Here is a man after my own heart. He finished with:

“Get off the bridge.”

I started laughing mid-stride and did what everyone says not to do: ran fast for the entire downhill section of the bridge into Brooklyn.

I had planned on a pretty mellow marathon day—no rush, just go for a nice jog, easy pace, stop and say hi to a couple friends who would be out cheering, maybe hang out for a couple minutes with them. My friend Syd and I would be doing the race together, and the last time we did it, in 2019, we finished in a fairly leisurely (for us) 4 hours 50 minutes.

Then Syd strained his hamstring nine days before the race, and his 2021 race was in jeopardy. He spent the week in physical-therapy appointments, but by Friday, running more than a mile was still a no-go.

So he said he was just going to walk the whole thing instead. I said I wasn’t sure he would have much fun doing that, but Syd loves the New York City Marathon. He does not love running, but he was born here, and he loves the race that calls itself “the world’s marathon” and is also his hometown race, which he’s run a dozen times now. Every year he begins his day by getting on the 1 Train at the 66th Street station, getting off at South Ferry, taking the ferry to Staten Island, a bus to the start village below the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, and then running the race, crossing the finish line, and walking the few blocks back to his apartment.

Instead of running with me in the last starting wave at noon, Syd decided he’d leave with his assigned wave at 9:55 A.M. and have a two-hour head start on me. We did some rough math at a restaurant on Friday evening and figured there was a good chance we’d finish pretty close to each other, depending on how fast he walked and how fast I ran. And also if his hamstring held together and he made it to the finish line.

I had not prepared for the race very intelligently. I hadn’t run more than eight miles or so on pavement at one time the entire year, since I’d spent most of my time training for trail races. I’d just finished one of those races, a 100K, 22 days before. The previous Friday, I did the Presidential Traverse in New Hampshire with my friend Doug, covering 21 miles and 8,300 feet of elevation gain, during which I slipped on a wet rock and fell directly on my ass but also caught part of my fall with the ball of my left foot. Nothing was broken, but it was painful to go up and down stairs for the next two days.

I spent most of the Saturday before the race walking around Greenwich Village and drinking coffee, not wanting to spend my time sitting in an Airbnb with my feet up. A voice in my head started saying things like, “Maybe you should just try to run fast tomorrow.” Sure, Voice in My Head, I could do that. But it might not be—how would you say—something a smart person would do?

While drinking coffee at 5 A.M. the morning of the race, I committed to noncommittal: I’d “just” “kind of try” to “run a little faster” at the beginning and see how it went. Maybe I’d feel good and keep going. Maybe I’d feel like garbage and decide to settle into a slower pace. Either way, I figured best case I’d break four hours, and worst case I’d come in around 4:20 or 4:30. A few years ago, I ran a bunch of self-guided marathons throughout the year, and if it was reasonably flat and I was feeling good, I could usually finish a marathon in about 4:20. Once I went really hard and ran one in 3:48, all by myself, in the park, carrying 60 ounces of water. So in theory, I could maybe do it again?

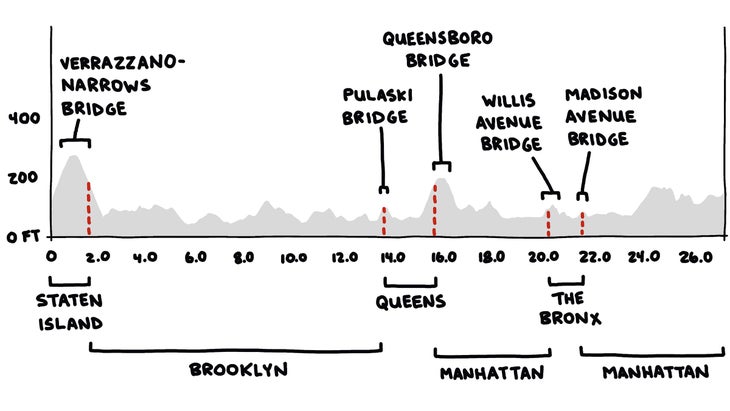

It is impossible to exaggerate the energy of the New York City Marathon spectators. There are truly very few sections, and of short distances, in which you are not being watched, encouraged, cheered at, or serenaded by either a live band or a DJ. Almost all of those sections are on the five bridges you cross: the Verrazzano, from Staten Island into Brooklyn; the Pulaski, from Brooklyn into Queens; the Queensboro, from Queens into Manhattan; the Willis Avenue, from Manhattan into the Bronx; and the Madison Avenue, from the Bronx back into Manhattan. Lots of marathoners walk the uphill sections of the bridges, so the slowed group speed, plus the relative silence, plus the uphill grade can make the bridges feel long, arduous, and morale dampening.

The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge drops runners into Bay Ridge, the beginning of the Brooklyn section of the race. I had run fast enough up and down the bridge that I could only see a few runners ahead of me, all of us spread out by a hundred feet or more, as we started to encounter the first of the spectators lining the streets, cheering and holding signs welcoming us to Brooklyn. With how spread out we were—thanks to the 2021 marathon having only 30,000 entrants compared to 53,000 in 2019—and the starting waves staggered with more time in between, the early spectators really felt like they were cheering just for me.

I have spent much more of my race time running trail ultramarathons, which require lots of hours plodding along in solitude with few distractions from the pain in your legs and the number of miles you have left. The New York City Marathon is on the opposite end of the spectrum: you experience a sensory bombardment that might be a bit terrifying if it didn’t feel so positive and uplifting the entire time.

In several sections, the roar of the crowd is loud enough and close enough that earplugs would definitely not be a ridiculous idea. Most of the time spectators stand well back from the street, but in many places, they narrow the race course, drawn in by the gravity of the runners, their enthusiasm pushing them unconsciously forward. At one point in Williamsburg, the course tightened into a tunnel of screaming people, leaving only 15 feet or so for runners to squeeze through. Some people hold out paper towels or tissues for runners to grab as they pass, or half bananas, or candy, and sometimes spectators have bought a case of water bottles to hand out.

I have never left my house to go cheer for people running any sort of footrace, and I don’t know if I understand what motivates people to do it, but I am thankful that they do it. I don’t know why they care if perfect strangers feel encouraged and/or even loved for a few hours as they struggle through the streets—all I can say is that I have never felt so supported doing anything in my entire life as I have in New York during the marathon. I imagine it’s something like a basketball player feels as they step up to the foul line with the chance to put their team ahead with one second remaining on the clock, and the crowd stands up, cheers, claps, and fills the arena with noise—but when you’re running the marathon, there’s no possibility of letting anyone down. The ball will not bounce off the back of the rim. You just keep moving forward. Even if you staggered and passed out on the street, I have a feeling you’d be immediately carried off the course and to medical assistance within seconds by two to six New Yorkers. Actually, they might just pick you up and half-carry you down the racecourse until you got your feet under you again. Who knows.

A few years back, I was exiting a subway station somewhere in the Bronx, plodding up a flight of stairs a few feet behind an older woman carrying a shopping bag. At each step, she would set the bag down on the next step, then move her feet up, slowly going up the stairwell, holding up everyone below her on the stairs as we waited. Suddenly, a man stepped out from behind me and walked into the flow of people coming down the stairs. He reached over and took the woman’s shopping bag out of her hand without saying a word, and then quickly charged up the last eight or ten steps. At the top of the stairs, he set the shopping bag down and walked off, without even a glance back. When she reached the top of the stairs, the woman picked up her bag and carried on.

As we were waiting for the race to start that morning, I joked to Syd that I thought it would be hilarious to carry a huge map of the racecourse for the first couple miles, holding it out in front of you and saying things like, “We go straight here” and “We turn left up ahead somewhere.” Syd laughed and said it would be impossible to get lost during this race, and I think he meant literally but maybe also spiritually, in a sort of collective New York humanism way.

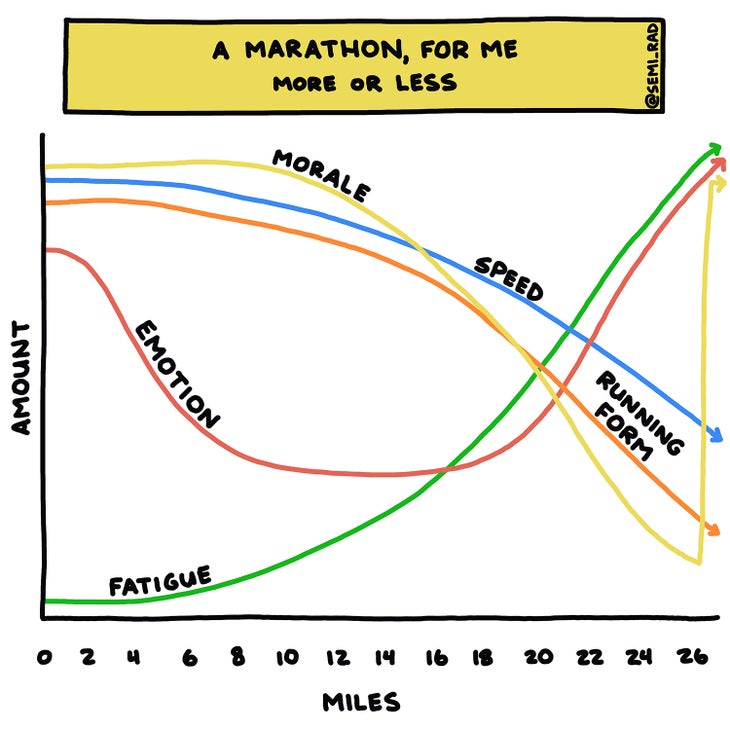

One way to look at a marathon is that you’re going to feel like shit eventually, and you’re just trying to hold it off as long as possible. You hope it doesn’t happen until mile 23 or 24, but if you go out too fast, you can find yourself in a bad way much sooner than you might expect. I went out too fast.

I did not research any sort of race strategy or consult any sort of expert or coach. I just thought that morning that I’d try to run a bunch of nine-minute miles early on in the race and get them in the bank, so to speak, and the more nine-minute miles I ran, the closer I’d be to a sub-four-hour pace. Maybe I could afford to take it a little easy near the end and jog some ten-minute miles if I didn’t waste too much time stopping to refill my water bottle and/or talking to people.

I stopped to pee once, around mile eight, picking the absolute worst Porta-Potty on the racecourse, the inside of which had been sprayed by, well, someone having a much less gastrointestinally stable day than me. I bolted in and out as quickly as I could, rubbing way too much hand sanitizer on my hands as I ducked the tape to head back onto the racecourse.

I stopped to talk to friends in Fort Greene, maybe for a minute or slightly less and again around mile 16, just after the Queensboro Bridge, when my friend Greg handed me a banana, effectively paying me back for the banana I’d given him when I was watching the race and he was running it in 2014. I grabbed water at several of the later water stations, and a full-size Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup, and a bag of M&Ms from a guy handing out leftover Halloween candy around mile 17. And then at about mile 21, someone yelled my name from the right side of the racecourse: Syd. I stopped to walk with him for a few feet, checking in on how his hamstring felt and enjoying just not running for a while. I was very, very tempted to chuck my whole idea of running fast and simply walk the rest of the race with Syd. But he told me to keep going, so eventually I started jogging again.

By that point, with five miles left, I was starting to drag. I tried lying to myself, saying things like, “I feel strong” and “I feel good” in my head as my muscles stiffened and I was sure my “running form” was starting to look like the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz. And then at mile 23, the racecourse climbs the hill up Fifth Avenue, because, well, fuck you. That’s what the course has always done and probably always will do as long as they have this marathon, and if it makes you sad and want to cry because you’re tired, that’s just the way it is, but to finish the race, you still have to drag your carcass up it one way or another. People, myself included, were struggling. I tried to pass as many as I could, hoping the mini-sprints to get around other runners might keep my per-mile pace at a respectable speed. A woman who was at least six months pregnant, wearing a shirt reading “Baby on Board” on the back, appeared, and I paused to tell her nice job, because OK, I was really trying hard and going through an intense personal struggle here at mile 22, but not, you know, constructing a human being in my abdomen during the marathon.

We turned into Central Park at 86th Street, and the spectators were all there, screaming, standing mostly off to the side but sometimes almost in the way, looking for their friend or family member, and they were all clean and showered and not sweaty and wearing nice clothes and just in general the complete opposite of how I felt and looked, and I kind of wanted them to all go away so I could just do this last bit of suffering to the finish line in private. Time slowed down, and minutes started to take twice as long as they did earlier in the race, and oh fuck me, that’s right, there are a couple more little hills, ugh.

Then all of a sudden we turned onto Central Park South, and out of nowhere I caught a sob in the back of my throat, something in the way the whole scene in front of me was framed and happening, and I don’t know where it came from, and for a second I thought I might just start weeping in front of all these strangers as I ran the last mile, but I didn’t really care if I did or if they cared or noticed, and two breaths later it just disappeared. My legs fucking hurt, and I kept trying to tell myself to lift my knees, but it felt like I was running in sand. Yet I wasn’t; I was still making progress. I looked at my watch and I had plenty of time, and unless I somehow tripped and fell and knocked myself unconscious in the next 14 minutes, I would finish in under four hours. Which is a totally arbitrary measurement of velocity over a semi-arbitrary distance some guy in ancient Greece allegedly ran once, and then we somehow decided that hundreds of cities around the world should create mass running events of that same distance, including New York. And all of that would be a lot to explain if an alien landed here and ran up next to me on Central Park South and asked what I was doing, and that’s a weird thing to be thinking about, but so is almost bursting into tears after running for 3 hours and 50 minutes straight for no real reason.

Just after the last turn into Central Park at Columbus Circle, a few people could obviously smell the barn and found an energy reserve and were able to pick it up for the final one-third mile to the finish line. I was unable to find any such motivation. I felt—and also looked, as the official race photos later confirmed—like someone who had just woken up from a monthlong coma and started wandering around the hospital. If I had looked down and seen that my legs had somehow turned into wood, I would not have been surprised. I jogged across the finish line, stopped my watch, took a quick selfie and texted it to my wife with the words “Hello I am dead” and shuffled along with all the other finishers, through the volunteers handing us bags containing drinks and food. I accepted a post-race poncho from a volunteer and made my way over to a curb, where I thought I might sit down for a few minutes and chug the Gatorade, recovery drink, and bottle of water in my bag, but when I tried to bend my knees more than 25 degrees in order to sit down, it became clear that I would not be able to get up from that position.

So I kept shuffling, joining the almost silent procession of blue zombies making our way down the park drive to 72nd Street. Heads were down, no one was talking, because they were either too tired or because they were texting their people about their finish and/or where to meet up to sit on furniture and consume calories immediately upon exiting the park. I checked the app to see where Syd was, and he was only a few minutes behind me. At 72nd and Central Park West, long rows of benches lined both sides of the drive, and I found a spot behind a group of police officers and gingerly lowered myself halfway down, then plopped onto the bench. For a second, I thought I might be able to wrap myself up in the poncho and sleep here for a few hours.

After a few minutes, Syd appeared, walking up the drive, looking no worse for wear than when I’d seen him a few miles ago. He asked how I felt, if I’d finished in under four hours, and then said, “I popped my hamstring twice in the last quarter-mile.” I said “Uhhhh what, is it really painful?” He said, still half-smiling, “Oh yeah.” We stopped in front of the last official race photographer to get our photo together and then walked out of the park, heading for the medical tent to get some ice. Syd said, “That was the dumbest thing I’ve ever done, and it was also the most amazing thing I’ve ever done.” And then:

“I think I realized today that I don’t need to do any other races—this is the greatest race in the world.” I understood what he meant. He just loves the experience—the crowds, the city, the runners, the whole journey. But I simultaneously thought, “That is exactly the kind of attitude that pushes you to the point where you think it’s OK to injure yourself in the last 400 meters of your slowest marathon ever, Syd.” And honestly, I have a hard time blaming him.