Why Sprinters Don’t Have the Fastest Finishing Sprint

6 min readIf you haven’t rewatched the epic ending-straight duel in between Paul Tergat and Haile Gebrselassie from the 2000 Olympics not long ago, do yourself a favor and simply click below. All right, now you’re in the temper for one particular of the perennial running debates: where by do astounding kickers like Geb get their incredible kicks from?

There are 3 most important schools of assumed. A single is that dash speed is the prerequisite for a rapidly dash complete, an concept lately fleshed out by proponents of the speed reserve strategy. A second is that the fastest finishers are just people who are the very least fatigued at the end of the race, so fantastic endurance is the crucial. A 3rd is that it’s all in your head—that Geb’s ability to narrowly outlean Tergat approximately every time they raced is greatest spelled out by distinctions in self-belief instead than physiology.

But perhaps there is a superior clarification. A staff of scientists led by Brett Kirby of Nike Sport Investigate Lab, together with collaborators which includes Andrew Jones of the University of Exeter, who worked with Kirby on Nike’s Breaking2 challenge, a short while ago printed a paper in the Journal of Utilized Physiology that utilizes a uncomplicated mathematical design to predict how pacing strategies influence runners with various strengths and weaknesses. The product makes a entire pile of intriguing insights, but the one that grabbed my attention was its skill to correctly predict how rapid each individual runner will operate the remaining lap of a supplied race.

The paper was motivated by the men’s 5,000- and 10,000-meter activities at the 2017 Environment Championships, the place the overpowering favourite Mo Farah, unbeaten at significant championships around these distances given that 2011, defended his 10,000 title but was outkicked by Muktar Edris in the 5,000. Was there some thing in the way the two races played out that made individuals outcomes? And more importantly, the scientists puzzled, could the outcomes have been predicted in advance?

The model that Kirby and his colleagues use depends on a concept referred to as significant speed. I’ve prepared about it a couple periods in advance of, and the total examine is free to read on-line for these who want to dig into the information. For our applications, vital velocity is mainly a threshold that divides metabolically sustainable initiatives from unsustainable types. After you’re likely quicker than crucial velocity, as races among 800 and 10,000 meters inevitably do, the clock is ticking down to your eventual exhaustion. How extended that will take, or equivalently how a lot power you can expend over that significant threshold, relies upon on a second parameter—a sort of spare gasoline tank—that is sometimes termed anaerobic ability. (The terminology is controversial for different complex explanations, but I’m likely adhere with anaerobic ability for the reason that I never know of any better selections. In the paper, they just simply call it D’, and it is expressed in units of distance. I like to consider of it as the most distance you could sprint just before keeling above if you held your breath, but which is a metaphor rather than a physiological explanation.)

The paper analyzes the success of each the 5,000- and 10,000-meter races from individuals 2017 championships. For each athlete, the scientists calculate a critical speed and an anaerobic potential dependent on preceding race results (as explained in this article). Those parameters give you a prediction of who would get the race—but that prediction assumes that everybody is likely to run a beautifully even tempo that maximizes their particular capabilities, by operating just plenty of a lot quicker than their crucial pace to exhaust their anaerobic potential as they cross the complete line.

That is not how things do the job in the true planet, though—because the rate may differ consistently based on who’s primary and what tactics the runners are employing. If the preliminary speed is rapid, it will power runners to get started burning up their anaerobic reserve proper absent, which favors rivals with superior crucial velocity. If the initial rate is gradual, then the race will occur down to a late burn up-up that favors people with substantial anaerobic potential. This isn’t a significantly deep insight: rapid races favor aerobic monsters and slow races favor kickers.

But genuine-lifetime championship races are rarely all speedy or all gradual the tempo differs continually as runners surge, relax, and counterattack. Just about every runner’s unique anaerobic reserve is draining any time the tempo is more rapidly than their special significant velocity, and recharging when the speed is slower. Applying the lap-by-lap splits of the 2017 championship racers, Kirby and his colleagues are ready to recalculate the place each and every runner stands immediately after each and every lap. At the start out of the race, realizing the runners’ significant pace and anaerobic reserve does not give you a pretty very good prediction of what order they’ll eventually complete in. But with each and every passing lap, the prediction receives far better and better—until, with 400 meters to go, the quantities give you a close to-fantastic forecast of how the race will participate in out.

In portion, the prediction gets superior because weaker runners fall off the pace as their anaerobic ability hits zero. That’s what happened in the 10K, so there were being only six guys remaining in competition for the remaining lap. In the 5K, which was a slower, a lot more tactical race, the total industry was still in the blend at the bell. In equally cases, the finishing order—and, to a impressive extent, the instances for the remaining 400 meters—were predicted not by who was the fastest sprinter or had the most effective stamina, but by who experienced the most anaerobic ability still left at that correct moment in time, following 4,600 or 9,600 meters of surges and countersurges.

The end result? With a lap to go in the 5K, Muktar Edris was favored to get, regardless of commencing the race as the fourth seed, according to the product. Yomif Kejelcha, the model’s prerace favorite and the runner who, in real life, was major the race as the remaining lap started out, was now predicted to complete only fourth dependent on his depleted anaerobic ability. Farah was picked for next, with American Paul Chelimo, who experienced fallen back again to sixth, picked for 3rd. That’s exactly how it played out: the model effectively predicted the locations of all 9 runners for whom it experienced enough pre-race facts to estimate their critical pace and anaerobic capability.

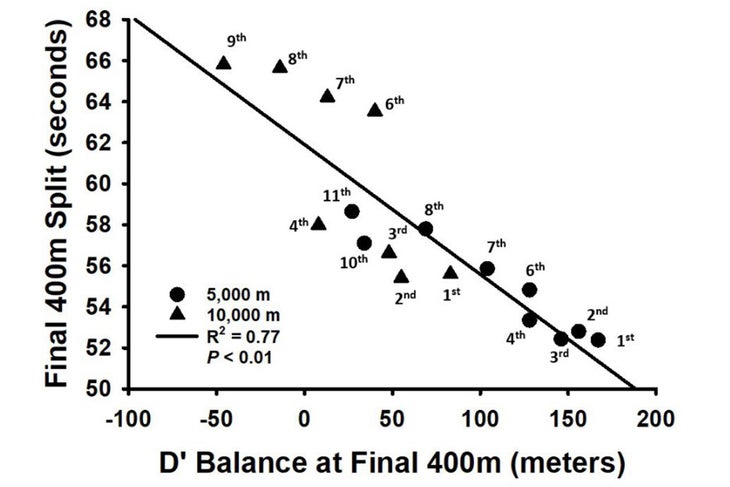

Here’s a graph showing time for the final lap as a perform of anaerobic ability remaining at the start of that lap (that’s D’, shown as a length in meters):

The higher the remaining anaerobic ability, the faster the last lap. It is not fantastic: you can see that the third-spot finisher in the 5,000, Chelimo, really shut marginally more rapidly than the two guys in advance of him, even with having much less D’ to burn. But in general, it is uncannily accurate at predicting the notoriously difficult-to-forecast finishing kick.

The key level listed here is that neither endurance nor sprint speed, on their very own, would have pegged Farah as a around-unbeatable championship runner for 6 years. He did not have the best significant speed in both the 5K (that was Kejelcha) or the 10K (that was Kenya’s Paul Tanui). He had only the fourth-largest anaerobic ability in both equally the 5K and 10K. But he in some way mastered the art of using the razor’s edge of his vital speed and controlling the closing stages of races in order to get to the previous lap with the most anaerobic potential still left.

The stage? Probably if you know someone’s vital speed and anaerobic capacity (which can be estimated from their best race instances at a few distinctive distances), you can devise the best system to conquer them, depending on irrespective of whether you have a much better essential pace or anaerobic potential. Maybe, for superior or worse, we’ll eventually have true-time estimates of anaerobic capability shown on our wrists as we race. But I’ll confess: no subject how lots of instances I check out Geb reel in and then outlean Tergat, I’m nevertheless not certain there’s any physiological model that can completely seize that magic.

For far more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, indication up for the e mail newsletter, and test out my guide Endure: Brain, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Boundaries of Human Functionality.